STRUCTURAL DEPENDENCY

Opened by Dr. Ric Spencer

Curated by Tom Mùller

Images by André Avila

Choreography by Brooke Leeder

Painting assisted by Bennett Miller & Cara Teusner-Gartland

Structural Dependency essay by Sheridan Coleman

August and orderly, the brick-and-render building on Lot 123 Fremantle has a zero setback from the public pavement, demanding a scuttle across the roadway to properly take in its stuccoed pediments, proud parapet and broad, square footprint.

In linguistics, the structure-dependency theory describes how meaning is not held in individual words, but in their relationship to one another in a sentence. Words depend on hierarchical systems, just as a keystone furnishes the soundness of a brick arch.

One certainly feels like a little word rattling around a sentence inside Pakenham Street Art Space. For many artists, it’s an intimidatingly hard-to-fill and inconveniently expressive gallery. Even broaching the threshold is affecting: the temperature drops; darkness mutes your eyesight; the atmosphere is dewy; sounds land differently. One toys with the idea that a subtly unfamiliar version of earthly physics governs this room.

Constructed in 1910, this Federation establishment has harboured Fremantle’s most historic industries, as a warehouse for the wool trade, shipping and the arts. It’s occupants—Paterson & Co., Elder Smith & Co., Frank Manford Pty Ltd and PSAS—have all been local, making the building a stalwart constituent of the peculiarities of commercial and creative endeavour in West-End Fremantle. Today artists bustle and nest upstairs and the whole structure leans on engineered braces, which pause its gradual but determined pitch north.

Any skinflint graduate artist can tell you that gallery invigilating is as close as you can get to becoming part of the architecture. One learns where to stand to best intercept a draught or to eavesdrop on visitors unnoticed. Invigilation enkindled Matthew Thorley’s relationship with PSAS. In stillness and solitariness, the artist became aware of the fabric of the building, the sensations and phenomena emanating from it.

Questions materialised. What had this place experienced? Was some mark or memory of that still here? Thorley began to see the building as a person, growing old and accumulating scars and stories. It had habits and rhythms; it tensed, relaxed, warmed, cooled and creaked; its voice could be known.

Over six months, Thorley prepared to unravel the nature of the old warehouse. This did not mean reaching for the blueprints or heritage register, but was an in situ process requiring long visits, exploratory caress and quietude. It was an ascetic residency. Thorley tolerated the discomfort of inertia and eschewed thoughts of the outside. He learned to soften his gaze.

Hold your hand up against a contrasting surface. Unfix your focus. After ten seconds, the colour of your hand will flatten. After thirty, it’ll vibrate, ripples of light swimming at its edges. After a minute, even closing your eyes won’t banish its silhouette from your vision. Relaxing the eyes reveals how the brain translates and simplifies the visible world. At PSAS, Thorley was unpicking this unsigned-up-for optical condition, instead asking his brain to show him everything, to let him sense the raw strangeness of perspective, movement and proportion unedited.

Thorley found that buildings have a kind of direction or inclination. They move, sure, but these movements are responses to sensation: to existing in the world. Two centuries earlier, Arthur Schopenhauer studied the same idea. The German philosopher wrote that from our bodily intuition, we learn that a person is nothing but a set of blind, insatiable desires and drives (or, The Will). This, he said, was true of all things. A building was an objectification of The Will, or as Thorley puts it, all objects aspire to movement.

“The pillars are doing all the work,” the artist says, patting one in a gesture of appreciation and deference. In Thorley’s company, the improbability of the building really hits me. A staggering tonnage of steel, brick, Jarrah and cement is entwined so as to withstand time, gravity, usage and nature, allowing me to stand inside, uncrushed. How is it that we so easily forget what buildings do? That they alone enable safekeeping, privacy, controllable conditions, quiet, storage and comprise our most lasting demonstrations into posterity. Adding their beauty, is this not everything?

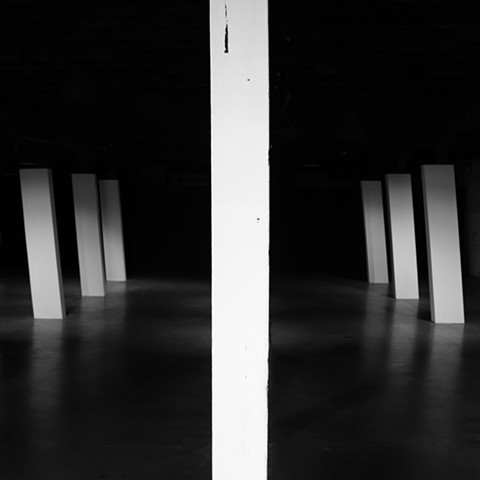

Thorley’s monochrome interior construction is paralleled by a 45-minute dance performance developed by Perth choreographer Brooke Leeder. Together, the works echo the rhythm and movement of the architecture and the people passing through it.

At first glance, Structural Dependency appears to consist of twenty-two finely built pillars and a four-night dance season: formal, contemporary works grafted onto a historic space. In truth, these works are just the final cadence in a long, devotional engagement between Thorley and the building. What this exhibition means for the visitor, is time: time for a little encounter with a stately, eccentric structure.

In my own encounter, hushed and unhurried, and I found I was not too coy to elicit wooden thuds from the pillars, or to lie down and appreciate the loveliness of scattered drill holes in the ceiling. I spotted pins lost in a crevice, and left them there, intuiting that they belonged to the building. Each visit will engender its own discoveries. Though you might have forgotten, like I had, to marvel at buildings, it matters little, because Lot 123 still stands and it is forgiving. Make yourself quiet and listen to it croon.